Category Archives: Reviews (movies)

To Kill A Mockingbird

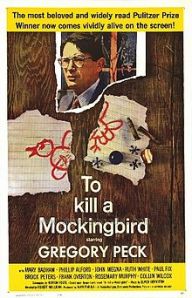

To Kill A Mockingbird

To Kill A Mockingbird is a meticulou sly-made and critically- acclaimed movie. It not only truthfully depicts the goodness of human beings, their courage as well as innocence but relentlessly reveals the depth of their ugliness and racial intolerance. With the marvelous and natural performance of each character, carefully-crafted dialogue, and good structure and pace, To Kill A Mockingbird stands the test of time and never fades out of this capricious film market.

sly-made and critically- acclaimed movie. It not only truthfully depicts the goodness of human beings, their courage as well as innocence but relentlessly reveals the depth of their ugliness and racial intolerance. With the marvelous and natural performance of each character, carefully-crafted dialogue, and good structure and pace, To Kill A Mockingbird stands the test of time and never fades out of this capricious film market.

As soon as the movie starts, the audience feels as if they were sent back to 1930s Alabama. The acting is incredibly excellent, vivid, and convincing. Every character is true-to-life, even children, whose performance is usually flawed due to the young age. Jam and Scout, the two main characters, are neither the stereotypical, ridiculous good-for-nothing brats, like Dudley Dursley in Harry Potter, nor the angelic and somewhat super-powerful prodigies, like Potter himself and Frodo in The Lord of The Ring. Jam and Scout are just two normal and innocent kids that we can see everywhere in our daily lives—so real and thus touching.

The dialogue was wittily written. Humorous. Meaningful. For example, when Atticus compliments the old woman, “You are like a picture,” the children behind his back mutter, “A picture of what?” Children’s wittiness and a father’s tolerance are fully displayed in this short dialogue. This movie is powerful in its language. In the courtroom, when Atticus is leaving, the old man demands Scout to stand up, saying “ Your father’s passing.” Those three words tug at my heartstrings.

In addition to the attractive acting and dialogue, the structure and pace of this film also deserve high praise. Every scene and every event has its own place, functioning properly and closely with each other – Nothing is trivial, unimportant, and grotesque in this film.

With marvelous acting, dialogue, structure and appropriate pace, To Kill A Mockingbird outshines the rest of movies which also deal with the clichéd topic of “racial discrimination”, and proves itself as a timeless masterpiece.

Picture from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_Kill_a_Mockingbird_(film)

What We Can Learn from Transamerica –Analyze Gender Issues in the Film Transamerica

What We Can Learn from Transamerica

–Analyze Gender Issues in the Film Transamerica

This report explores the recurring themes of the 2005’s film: Transamerica – sex versus gender, female transsexuality, and gender stereotypes. It aims to challenge some mainstream values that our heteronormative culture embraces and provides new perspectives for dealing with today’s increasingly complex gender issues by examining theories from Gender and Sexuality (Michael Ryan, Brett Ingram, Hanna Musiol, 2010), Gender Trouble (Judith Butler, 1999) and The Apartheid of Sex (Martine Rothblatt, 1995).

The film starring Felicity Huffman from Desperate Housewives centers on hardships and triumphs of a male-to-female, transsexual Los Angelan, Bree Osbourne, formerly known as Stanley Chupak. Before Bree’s last sex reassignment surgery that involves the change from penis to vagina, she receives a phone call. It is from Toby, a son she has never seen and a product of her youthful dalliance into a heterosexual relationship. Bree then flies from L.A. to New York to meet him. Toby turns out to be a troubled teenager who lives with drug addicts and supports himself by shoplifting and hustling. Desperate to escape from his sexually abusive step-father, he embarks a trans-American journey with Bree from New York to L.A., with hopes to find his biological father. Along the ride, audience sees hereditary secrets disclosed, family values crashing with individual independence, and more importantly, social intolerance for incongruity between sex and gender.

This poster illustrates the inner struggles of our main character, Stanley/Bree. We may feel safer to claim Stanley as a man, but how about Bree? Is she a woman or a man? Is the use of pronoun “she” inappropriate? What should a man/woman do? If we say a woman should wear dresses and look after children, then Bree is certainly qualified. (She is extremely self-conscious and dresses like a princess even in the wilderness. She also takes care of her new-found son along the way.) If we say a man should have one special part of human anatomy, then Bree is qualified again. (Toby sees her penis when she urinates.) So, let’s circle back to the question: is Bree a woman or a man? (By the way, “Stanley” always reminds me of the alpha male in A Streetcar Named Desire.)

Before we answer the question, we may want to explore the dichotomy between sex and gender first. “Gender ought not to be conceived merely as the cultural inscription of meaning on a pre-given sex.” (Judith Butler, 1999) “At birth a cursory examination is made of a baby’s genitals. If the doctor sees a small penis, the parents are told, ‘It’s a boy!’ A small vagina, “It’s a girl!’” (Martine Rothblatt, 1995) A few seconds’ glance at genitals, people are cast into an either-male-or-female sex type. If they are “boys” (with male sexual organs), they should be powerful, aggressive, dominant, brave, stoic, or simply “masculine”. Crying is not allowed, and is often associated with derogatory terms like sissies or mama’s boys. On the other hand, if they are “girls” (with female sexual organs), they are expected to be gentle, caring, family-centered, passive, submissive, dependent, in a word—feminine. Otherwise, they are considered as tomboys. This stereotype is manifest in the following statement: “Strong ‘masculine’ women are portrayed as Medusas or witches who harm men.” (Michael Ryan, Brett Ingram, Hanna Musiol, 2010) In other words, people are thrown off onto two railroad tracks— two parallel lines that never cross— the minute doctors declare their sex type. Those tracks are often referred to as “gender development”. Straying from one’s designated track incurs punishment, repression, and even psychiatric treatment. (Bree has to consult a psychiatrist before the surgery.) Under this biology-is-destiny formulation, Judith Butler points out that culture, not biology becomes destiny.

Born as a boy (with a penis, to be exact), Stanley/Bree is constrained to the path of masculinity. Even though she always considers herself a woman and behaves like one, the society calls people the sex of their genitals. Thus, Bree’s whole life revolves around one goal: getting rid of her penis, as if it is the sole obstacle hindering her entrance into womanhood. Incongruence of sex (body) and gender (mind) is like a time bomb, ready to explode any minute. It brings on endless anxiety, desperation, and a sense of impending doom.

“What a tragic mistake, then, to construct a gay/lesbian identity through the same exclusionary means” (Judith Butler, 1999) We may stop here a moment and try to think outside the box. Who dictates us to categorize people into two groups—men and female only? (South Africa used to split its people into black and white, and decades later, this racial segregation is viewed as illegal and immoral.) In fact, as long as we look beyond the values our patriarchal society imposes, we see a gender spectrum, a continuum where people are free to rest in a spot they deem comfortable. “There are billions of sex types: from Rambo to Oprah, from Madonna to Costner, from deep blue to blood red, and a vast rainbow of androgynous possibilities in between.” (Martine Rothblatt, 1995) As to the reason why people choose a particular spot on the gender spectrum, it may be related to their background, socialization, mental propensities, and so on. These possible factors may also cause them to go for a career as a firefighter rather than a teacher, to pursue a life as a Christian instead of a Muslim, to vote for the Democratic Party not the conservative Tea Party. In short, this is all about personal choices—to become “male”, “female”, or somewhere in between (a wide range with countless variations). This is not a matter of right or wrong, but a matter of personal tastes. Hence, wondering whether Bree stands on the male or female side of the gender spectrum is pointless. Why don’t we accept the continuum nature of sex types?

As its name implies, Transamerica intends to transform America by shattering gender stereotypes and illuminating the complicated topic of sex versus gender and trans-genderism. Though Bree leads a rather unconventional life, this film tries to present an “ordinary” Bree – not just a transsexual, but a human struggling to find a niche in this world with her petty worries, doubts, emphathy, kindness, courage, love. She is like everyone else. She walks among us.

References

1. Ryan, Michael (with Brett Ingram and Hanna Musiol). Cultural studies: a practical introduction. Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

2. Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 10th anniversary edn. New York; London: Routledge,1999.

3. Rothblatt, Martine. The Apartheid of Sex: a Manifesto on the Freedom of Gender. New York: Crown, 1995.

4. Transamerica(film) on Wikipedia, 2011. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transamerica_(film)

Apocalypse Now

picture: IMDB (http://www.imdb.com/media/rm71276800/tt0078788)

picture: IMDB (http://www.imdb.com/media/rm71276800/tt0078788)

Apocalypse Now

Apocalypse Now starts with a mixture of sounds—the sound of helicopter rotors, the sound of the ceiling fan whirring in the hotel room, and the song –“The End”. “This is the end…” as the song progresses, the intensity steadily heats up in the small sultry room. Staring up at the fan, Willard the Captain grows more and more agitated, but he remains immobile in bed as if being transfixed by the apocalyptic scene.

“I wanted a mission. And for my sins they gave me one.” As a veteran, Willard surly witnesses how frail, miserable, irrational a person can be in the battlefield and how costly, deadly, futile a war is. Deep in his heart, he knows the essence of wars but yet fails to muster his courage and to face this excruciating truth. He is ceaselessly haunted by his memories and nearly crippled by his guilt. (He kills or at least holds responsible for the deaths of 6 people.) Therefore, his mission to terminate the “murderous and dictatorial” renegade, Kurtz, is more like a journey of redemption than a simple military job.

Nevertheless, as Willard reads more and more dossiers on Kurtz and ventures deeper and deeper into the river valley, he bit by bit understands Kurtz’s determination to leave his motherland and the insanity of wars.

In the end of the film, the slaughtering of the bull is juxtaposed with the killing of Kurtz. Here, the murder is immensely deified and violence seems to become the surest/the most effective means to victory. To me, the ending is somewhat pessimistic. Except the killing, nothing is really done and the war seems to rage on. The never-ending circle of fear, hate, and retaliation will always thrive on mankind—a real apocalyptic scene comes into view, echoing the song, “This is the end…”